OPINION — In the late 1800s and early 1900s a disease termed cattle fever caused enormous economic losses to the cattle industry. It is deadly to cattle that have not developed an immunity, and the mortality rate is estimated to be up to 90 percent in these “naive” cattle. The disease was found to be transferred from animal to animal by a tick found in much of the southern United States. The only viable way to prevent the disease is to control the tick that spreads it.

Today, the disease and its vector, referred to as the cattle fever tick, are not well known to most Americans who reside outside of South Texas, even those who raise cattle for a living. That is because the tick was largely eradicated from the United States by 1943, preventing the spread of the deadly disease. A cooperative effort between ranchers and state and federal authorities pushed the tick back to Mexico and established a buffer that became the permanent quarantine zone.

For those landowners within a quarantine zone, there are several weapons to use against the ticks. We use controlled burning, reduce the population of non-native nilgai antelope and white-tailed deer through hunting, at certain times of the year we put out ivermectin-treated corn for white-tailed deer and we systematically treat our cattle using regimens prescribed by the Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program (CFTEP).

This program is administered jointly by USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC).

While cattle are closely monitored to prevent spreading the tick, growing wildlife populations can also inadvertently spread the tick as they travel in search of food and water. This is particularly true in the Laguna Atascosa and Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuges where the tick population has grown, largely unchecked. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) oversees the refuges and has begun taking steps to better control the tick on federal lands.

Previously, FWS only utilized controlled burning and limited reduction of some wildlife populations to help mitigate the tick resurgence. While this has been beneficial, additional tools have been needed to effectively control the tick on the two refuges. Thanks to TSCRA members working with USDA-APHIS and TAHC, FWS saw scientific evidence that supports the use of additional measures to eradicate the ticks on federal lands. These measures include using ivermectin-treated corn for white-tailed deer treatment and allowing cattle to graze the refuges.

FWS has recently started to allow ivermectin-treated corn on the refuges. The medicated corn kills ticks on white-tailed deer, one of the three major hosts for the tick. The treatment will not only improve the health of the deer population, but will prevent the deer from spreading ticks to adjacent properties.

FWS has also started to allow cattle to graze on the refuge. While it may seem counter intuitive, it is effective because cattle are preferred by the tick and unlike wildlife the cattle can be rounded up and treated year-round. Cattle still graze many of the over 550 refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System, and cattle grazing occurred on the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge from its founding in 1946 until 1974. On the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, a 2002 study found that grazing will have a mutual benefit to the refuge by reducing invasive grasses that threaten native habitats. Cattle will not only be a mechanism to eradicate cattle fever ticks, but will also reduce the risk of wildfires and assist the establishment and recovery of native brushland vegetation.

We thank the FWS personnel who are involved in in both maintaining standing eradication methods and expanding fever tick eradication efforts through the use of tools like grazing and distribution of ivermectin-treated corn. This is a huge achievement for the beef industry and an enormous relief for ranchers and landowners adjacent to quarantined refuge lands.

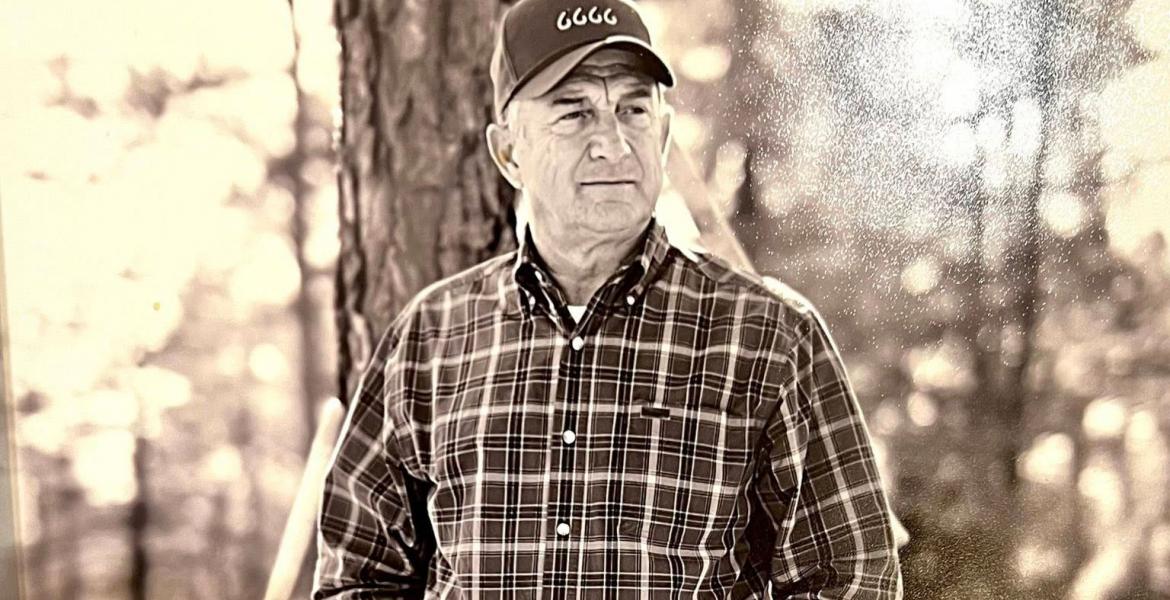

I manage a ranch in South Texas that is currently under quarantine. I know first-hand the challenges that are presented by fever ticks and can tell you definitively that the U.S. cannot afford to let cattle fever ticks expand into the range occupied in the early 1900s.

TSCRA members have fought hard to ensure the managers of the wildlife refuges will be using all the available tools. This will help all of us wage a better fight against cattle fever ticks.

Subscribe to the LIVE! Daily

Required

Post a comment to this article here: