When you’re looking to buy drugs in town, there’s usually a neighborhood for that. Old, decrepit houses with chipped paint line streets with little to no traffic posts, junk and debris are discarded haphazard in yards and alleyways, and a shambles of a sidewalk —if there’s any there at all—serves more as a safety hazard than a walkway. Every town has these areas—San Angelo included—and up until 2005, there wasn’t much the City could do about it.

When Bob Salas got hired as Director of Community Development for the City of San Angelo that year, one of the first jobs he was given was to develop a neighborhood revitalization plan that addresses the issues of the city’s ‘slums’.

As his first order of business, Salas needed a plan to put his neighborhood revitalization in motion, and that plan logically began with identifying target areas. He and the City organized a windshield survey—a survey reliant on systematical observation made from a moving vehicle—and four areas around elementary schools were identified as particularly problematic. Those areas were Rio Vista, Blackshear, Fort Concho and Regan.

“The first time I drove around…I was going down Blackshear, 11:00 in the morning, in my City truck,” Salas says. “I get stopped by some kids—youngsters—out there drinking beer at 11:00 in the morning. They stop me and ask me if I want to buy drugs. I thought to myself ‘we’ve got a problem here. If they’ll stop a city vehicle—I mean, there’s something wrong with that. That’s big city—that’s Chicago—that’s not San Angelo.’”

But it was San Angelo, back then. With the memory of the boys still fresh in his mind, Salas says that the City identified 47 disheveled houses being used for illicit purposes, then joined forces with a military organization to get started on a systematic clean up of the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods.

“We partnered with the National Guard and we knocked down 47…vacant, abandoned houses that were being used for crack houses,” Salas says. “In fact, it was called Operation Crackdown. A lot of the drug dealers had to scatter and go somewhere else. Right away, it started making the citizens feel safer.”

Salas said that following the cleverly named operation, he began receiving phone calls of gratitude, but still, one of the neighborhoods he’d identified as worst was still being neglected. That neighborhood was Blackshear, where he’d met the young beer-drinking boys during the windshield survey.

“It was almost systematically neglected,” Salas describes. “They had no sidewalks, no stop signs, no street lights. The roads were deteriorated. We started focusing on that. We took all the funds that were earmarked for housing and dedicated it to that; we took funds that were earmarked for streets and dedicated it to that area and got sidewalks, stop signs, those kind of things, he said.

“We started partnering with the private sector and we started building homes, started fixing homes, went out and got a tax credit project through the state…got money to build 36 brand new, single-family houses to embed in the neighborhood, and we got an award for it,” he said.

The award came from the Texas Municipal League and was bestowed upon the City of San Angelo in 2013 for spirit, knocking out metroplexes and other rural area contenders at the same time.

By 2013 of course, the neighborhood revitalization project had grown from an idea into fruition, and Neighborhood Blitz was the spawn of that. The blitz program focuses on spot-cleaning and keeping appearances up to improve life quality and dignity in troubled neighborhoods. Run by City staff and volunteers from ASU, Goodfellow and the community, the blitz program touches up minor aesthetic damage on home exteriors, removes junk and garbage from streets, and repairs doors and windows to a safe standard.

“No other city does it the way we do it,” says Salas. “We close down non-critical City offices and the personnel get allocated to…me and my staff.” The personnel are then divided up into teams which address certain areas, such as streets and alleys, and then pick up trash, cut brush, paint houses, etc. “We’ve collected over 700 tons of junk and debris,” Salas states as example. “We’ve collected over 600 tires.”

With a whole lot of spot-cleaning going on, however, some became concerned that they were putting a band-aid on a bullet hole, a dressing paid for with tax dollars.

“I had some serious questions about it.,” said Mayor Dwain Morrison of his position on Neighborhood Blitz two years ago at Tuesday’s City Council meeting. “I don’t remember whether I voted against it, but I had some serious questions about it,” he continued. Then, drawing long and emphatically on the next word, said, “However, I was wrong. I have seen the advantages this has done, because we have cleaned the neighborhoods up, and it seems like when one person starts doing something, then it’s who’s the next neighbor to start doing something. It’s kind of the domino effect,” he says.

Morrison said that his biggest concern had been a felt favoritism in the neighborhoods where blitz was taking place, a ‘why your house and not mine’ standpoint that may cause hard feelings among neighbors. He was also concerned that City staffers paid on the taxpayer’s dime were not in their offices during blitz projects.

In the absence of San Angelo City Councilman Winkie Wardlaw's usual skepticism (Wardlaw was absent), Councilman Don Vardeman spoke out in rare form at Tuesday’s City Council meeting, expressing opinions and concerns similar to the Mayor’s from two years prior when Salas showed up to ask for funds.

“I’m totally opposed to this,” Vardeman began. “I would rather fix up houses from the inside out than just this outside stuff…if you’ve got electrical problems, sheetrock problems, those people have to live in there. I would rather substantially repair an older person’s home, to make it safe, warm and comfortable for them than putting up siding,” he said, dismissing the blitz program as superficial.

Salas’ request had been to approve an amendment to the action plan for Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), annual grants disseminated by the Housing and Urban Development agency, which stipulates that the funds may be used in any fashion that benefits moderate-income citizens.

The funds have been used for a variety of things in the past, ranging from health issues to recreational centers, but this time Salas is seeking funding for housing.

“In the past we’ve used the half-cent sales tax affordable housing funds…to pay for the siding replacement. Unfortunately, those half-cent funds have dried up, so in order to continue the blitz, we’re recommending using CDBG grant funds. We’d like to move $102,969 from what we call complete rehabs to the annual blitz,” Salas explained.

Complete rehabs are the sort that Councilman Vardeman mentioned—renovations worked from the inside out, each with a cap of $25,000 on it. With the average blitz project costing circa $4,000, the impact is much more widespread, which Salas says is the objective of the program.

“As the funds get limited, it gets harder for us to do complete rehabs,” he says. “For $100,000 and the max is $25, how many can you do? Four. What impact is that? It’s great for the four families, but how about the rest of the citizens? You’ve got to do something for the city and for the neighborhood. I do neighborhood revitalization.”

To help allay some of Vardeman’s concerns, Salas reminded the Council that the blitz effort does offer an emergency repair program for internal and external issues, and that they fund Helping Hands, an organization that targets elderly homeowners and does more invasive work.

“I wouldn’t be opposed to taking this money and putting it toward them,” Vardeman said, still not convinced. Councilman Silvas then stepped in and suggested that the two organizations try to coordinate better, so that as much could be done as possible.

Noting the good the program is doing, councilman Silvas stated: “I’ve been a part of a couple of those blitzes. Not only do I see the morale of the staff—they’re fired up and ready to go that day—but I also the morale of the other volunteers,” Silvas began. “But at the end of the day, when I see that elderly lady and she has her house painted or just redone and I see those tears coming down—that’s all worth it.”

Silvas’ moving statement was enough to compel the Mayor ask for a motion to approve, which Silvas immediately made. Following a brief round of public comment all in favor of the blitz program, even Councilman Vardeman had been dissuaded from his original stance.

“I’m not against the blitz,” he said, “I just want to make sure everything’s out in the open.”

The Mayor called for a vote and the amendment passed, 6-0.

--

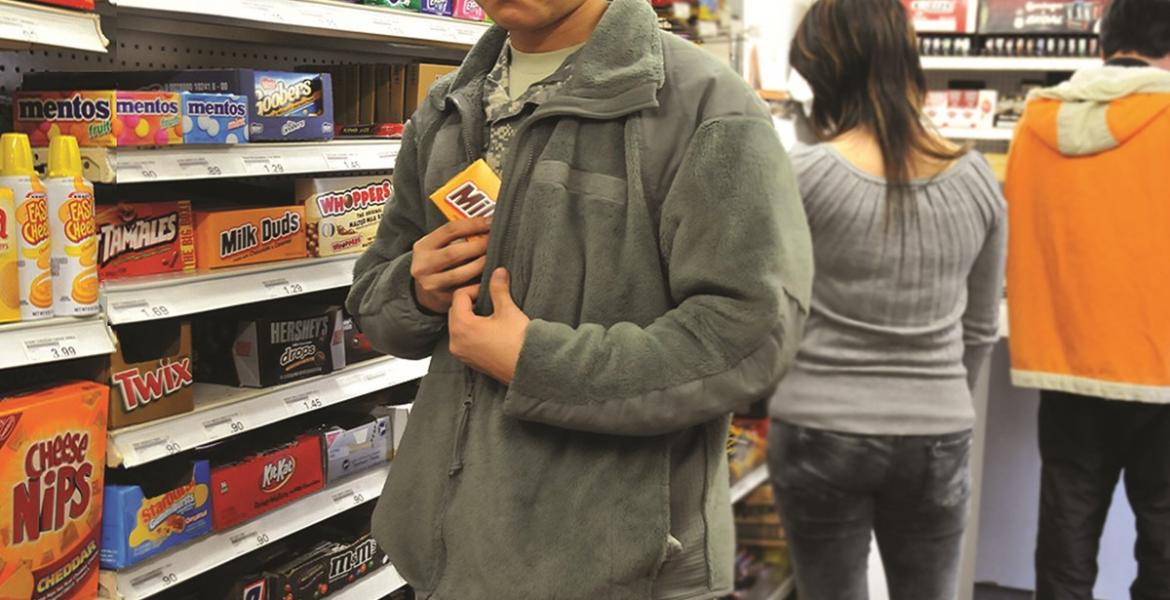

Editor's note: Although empty, dilapidated houses in any neighborhood can become distribution points for drugs, and they are commonly referred to as "crack houses," as interviewees have referred to them in this story, we do not want to confuse the reader into believing the home pictured on this story is a crack house. In fact, that's far from the truth. I have changed the headline from "San Angelo Cleans up Crack Houses" to "San Angelo Cleans up Dilapidated Houses," which is more accurate. Being a center for drug distribution is not a sole prerequisite to the Blitz tending to a particular home.

Subscribe to the LIVE! Daily

Required

Post a comment to this article here: