ELDORADO, TX — The latest buzz among urban economic developers in West Texas revolves around “Hydrogen Hubs,” where hydrogen can be extracted from groundwater and converted into energy. The technology promises significant potential, and the federal government is preparing to award billions of dollars in competitive grants to finance its development.

But ranchers who own land above the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer, which spans Kinney, Edwards, Sutton, Menard, and Schleicher counties, are raising concerns. The Edwards-Trinity Aquifer sustains vital water sources like Fort Clark Springs, San Felipe Springs, and Finnegan Springs. The latter feeds the pristine Devils River, one of the few remaining untouched waterways in the Southwest, originating in Crockett County.

This issue extends beyond the Concho Valley. The Edwards Plateau, covering a vast area of West Central Texas, includes the springs of the Comal River, San Marcos River, Concho Rivers, San Saba River, Clear Creek Springs (near Anson), and Anson Springs. The Edwards Plateau can be described as the land in West Central Texas lying north and west of the Balcones Escarpment fault line.

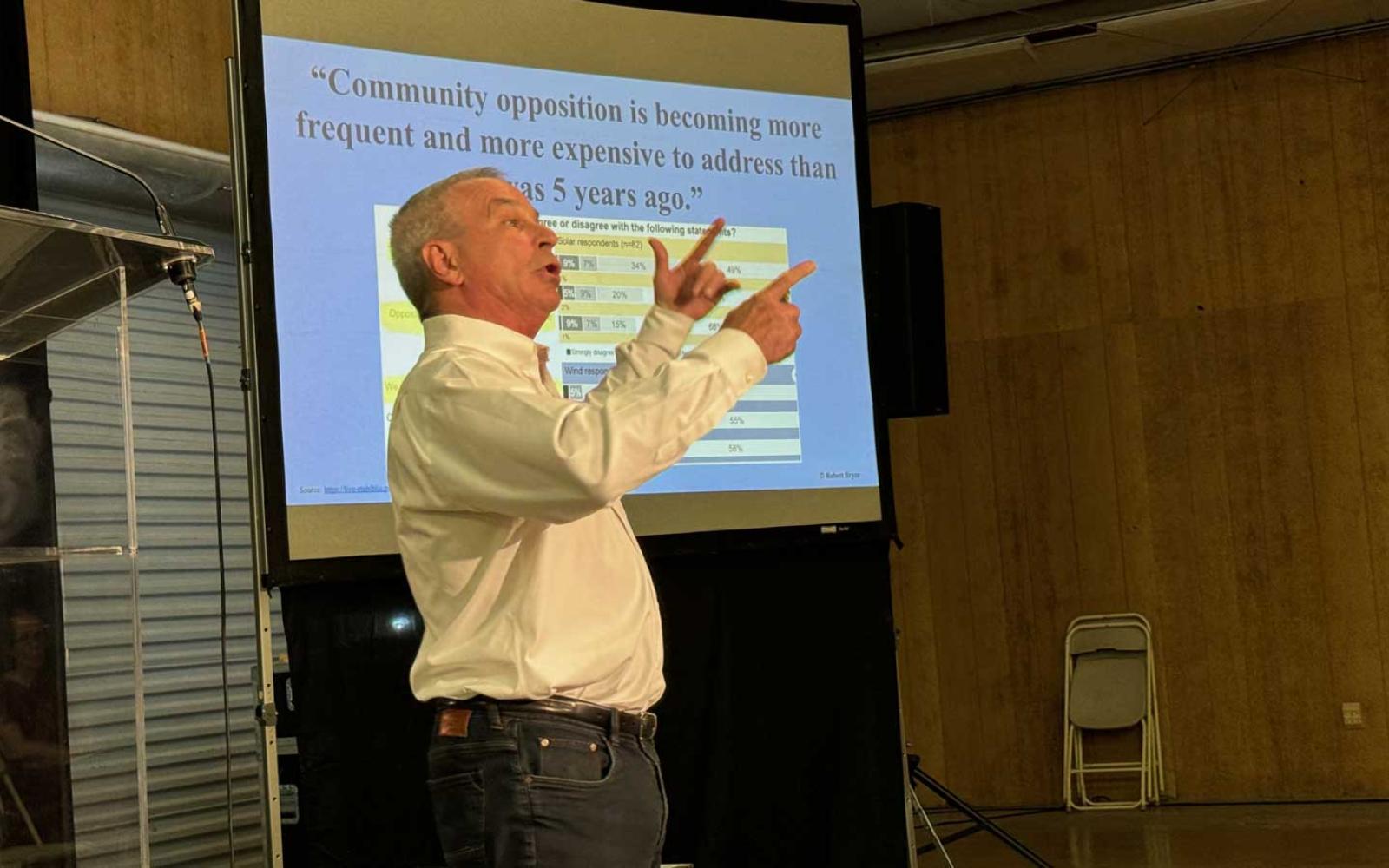

Robert Bryce, an Austin-based journalist who has been reporting on the alternative energy boondoggles for decades explained the industry is all about getting government subsidies, not "green" energy.

Concerned about the potential negative impact of alternative energy development on their land, ranchers have organized a 501(c)(3) nonprofit called the Edwards Plateau Alliance (EPA). Last Thursday night, 180 people attended a meeting organized by the EPA to discuss their concerns in Eldorado. Phil McCormick, a ranch appraiser, asked the attendees, “What do you want your land to look like in 50 years?”

Most alternative energy lease agreements span 50 years. McCormick, who began his career as a real estate appraiser in Eldorado, Schleicher County, after graduating from Texas A&M in 1970, recalled how ranches looked 50 years ago.

“Most people don’t want to stare at a thousand flashing red lights atop wind turbines for the rest of their lives while living on their land,” he said.

Phil McCormick, a ranch appraiser, asked the attendees, “What do you want your land to look like in 50 years?”

During the presentations, it became clear that a new alternative energy challenge is emerging: Hydrogen Hubs (H2 Hubs). The ranchers argued that despite the land pollution (wind turbines and solar farms) and water consumption required for these hubs, these expensive projects will not adequately address energy problems. According to them, it takes approximately 30,000 acres of H2 extraction, wind farms, and solar farms to generate the same energy as a typical pump jack in the Permian Basin. The U.S. government mandates that the energy used to extract hydrogen must come from alternative sources, making these H2 hubs a comprehensive but potentially problematic solution, requiring wind and solar farms to be collocated.

Transporting hydrogen from west Texas to market presents additional challenges. The pipeline must be pressurized, the ranchers said. According to the EPA, pressurizing the pipeline from the center of West Central Texas to Corpus Christi would require an H2 hub consuming 2,400 to 5,000 acre-feet of water annually in each county along the length of the pipeline to the Port of Corpus Christi. An acre-foot of water is 325,851 gallons, meaning 5,000 acre-feet equates to 1,629,255,000 gallons. To put this in perspective, San Angelo consumes 12 million gallons per day, so the water used for transport would exceed 4.5 months of San Angelo’s normal water usage in each county per year.

Pumping water for hydrogen production will strain the aquifer. Apex, a company seeking to purchase rights from ranch owners in the region, plans to start with three H2 plants that will collectively require 500 million gallons of water annually. These three plants are slated for construction in the Concho Valley. In total, three companies are competing for about 10 million acres and the water rights beneath them.

Food and Water Watch, a nonprofit dedicated to addressing food and water supply challenges, estimates that if hydrogen production meets the Biden administration’s 2050 goals, “Hydrogen production would consume so much water, it would equal the annual water use of 34 million Americans.”

McCormick emphasized that a ranch’s primary value comes from its water sources. Without water, a ranch cannot produce. In Texas, water rights laws—written before the state had 30 million residents—do not account for water preservation. If you own the land and the water, you can extract as much groundwater as you desire.

One idea proposed at the meeting was for the Texas Legislature to redefine water rights for “beneficial use,” meaning landowners could extract water needed for humans, animals, and farming while limiting excessive water harvesting.

The Edwards-Trinity Aquifer has long been a source of water harvesting stories. Oilman Clayton Williams was accused of draining so much water from the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer near Fort Stockton that Fort Clark Springs in Brackettville went dry in the early 2000s. Over the following decades, water harvesters have targeted the Kinney County Water District, seeking to sell water to metropolitan areas like San Antonio. In 2013, a water entrepreneur approached the San Angelo City Council with a proposal to build a pipeline from well fields tapping the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer in Val Verde County, a plan that drew significant opposition from Del Rio residents.

Furthermore, the U.S. Geological Survey has confirmed that the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer is hydraulically connected to the Edwards Aquifer, which provides drinking water for over 1.7 million people in Central Texas. Are you paying attention, San Antonio?

These alternative energy projects are not driven purely by entrepreneurial spirit to build a sustainable business, argued Robert Bryce, an energy industry journalist who spoke at Thursday’s meeting. Instead, they are fueled by U.S. government subsidies. Without these subsidies, these companies would struggle to survive is at all. However, with armies of attorneys and billions of dollars at stake, rural landowners are being tempted to join the “green energy” crusade.

A Schleicher County rancher issued a warning in an open letter to fellow landowners in the region:

“Many landowners in the early 1900s trusted the newly created oil companies, a decision many later regretted. We are in the same position today,” wrote Phillip Allard.

This time, however, the alternative energy companies have a mountain of taxpayer cash to wield as a weapon against the ranchers.

Dennis Grafa, who runs an insurance office at 1018 S. Abe. St in San Angelo, is the president of the Edwards Plateau Alliance.

Subscribe to the LIVE! Daily

Required

Post a comment to this article here: